Partner Spotlight | Peta India

Mechanical Temple Elephants Campaign

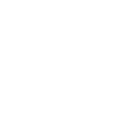

Khushboo Gupta

Director of Advocacy Projects | Peta India

Interviewed by: Nidhi Gupta

In a groundbreaking effort merging innovation with compassion, PETA India has launched its mechanical elephant programme, revolutionising traditional temple rituals. This project seeks to replace live elephants with animatronic counterparts, addressing critical issues of animal welfare and providing a humane alternative that preserves religious traditions without causing harm. The initiative stands firmly against animal cruelty, offering a cruelty-free solution for ceremonies and festivities.

Khushboo Gupta, Director of Advocacy Projects at PETA India, shares insights into the impact and future of this initiative. She highlights the plight of captive elephants and the urgent need for compassionate practices. This interview sheds light on the broader mission of PETA India to protect and respect animal lives, by encouraging temples across India to embrace this innovative approach and set a new standard in animal welfare.

Nidhi: Can you tell us about the launch of PETA India’s mechanical elephant programme and about the three elephants that have been donated so far?

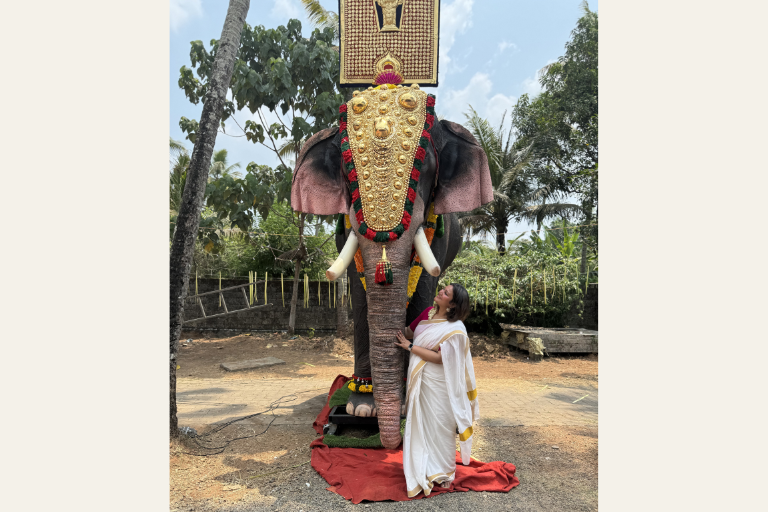

Khushboo: Following Irinjadappilly Sree Krishna Temple’s compassionate pledge to never keep or hire live elephants for rituals, festivities, or any other purpose, PETA India gifted them Irinjadappilly Raman, the first of three 3.5-metre-tall, 800-kilogram mechanical elephants, which will now help conduct ceremonies at temples in a safe and cruelty-free manner. These robotic elephants can flap their ears, swish their tails, move their eyes, raise their trunks, and even spray water with it – all without any suffering. Many notable figures, such as astrologer Padmanabha Sharma, tantri Karumathra Vijayan, and Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple priest Sadeeshan Namboothiri, attended the nadayiruthal (a ceremony to offer the elephants to gods) of Irinjadappilly Raman. Award-winning Indian film actor Parvathy Thiruvothu also lent her support to PETA India by presenting the innovative solution.

Actor Priyamani and PETA India then donated Mahadevan to the Thrikkayil Mahadeva Temple in Kochi in recognition of that temple’s pledge to never own or hire live elephants. The temple of Jagadguru Sri Veerasimhasana Mahasamsthana Math is the most recent temple to receive a mechanical elephant. Shiva was gifted to the temple by actors Aindrita Ray and Diganth Manchale as well as PETA India.

Nidhi: What is life like for an elephant kept in captivity?

Khushboo: When held in captivity for use in rides, films, weddings, festivals, and so on, elephants are stolen from their jungle homes and denied everything that’s natural and important to them. They are also kept in chains and forced to obey commands through beatings and under threat of weapons. As a result of their abuse, captive elephants often exhibit signs of severe psychological distress, such as swaying, head-bobbing, and weaving. Unsurprisingly, many lash out in frustration, injuring and even killing nearby humans.

Nidhi: How can we keep up with our traditions without the suffering that captive elephants endure?

Khushboo: The best form of worship of elephants, representatives of Lord Ganesha, is to allow them to live free, as God intended, with their families in nature.

With the launch of these three mechanical elephants like Irinjadappilly Raman, PETA India hopes to attract the attention of temples across India with our offer to help them transition to mechanical elephants and away from real elephants.

Nidhi: What are the statistics like for cases of elephant mistreatment in India linked to religious/traditional rituals or ceremonies?

Khushboo: In 2023, there were more than 2600 captive elephants in the country, according to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Project Elephant statistics. Approximately 1821 were used for tourism, entertainment, and religious purposes. Kerala, where temples’ use of elephants is extensive, is home to nearly one-fifth of India’s captive elephants.

Many of India’s captive elephants are under illegal custody, especially in Kerala. A one-day census conducted by the Kerala Forest Department last year revealed that only 32 of the 515 captive elephants paraded in festivals across the state have valid ownership documents.

Authorities commonly turn a blind eye to the illegal trade in elephants for use in temples or for rides and other spectacles, thereby encouraging the illegal capture of elephants in the wild. It is reported that the demand for elephants from temples in south India is directly encouraging poachers to capture wild elephants in northeast India.

All elephants in temples are mistreated, as they are chained near constantly, kept in solitary confinement, and controlled through use of weapons. Handlers typically break elephants’ spirits when they are young by separating them from their mothers and forcing them into a kraal (an enclosure or “crusher” in which they cannot move).

Nidhi: But since they are worshipped, aren’t elephants in temples well cared for?

Khushboo: Temple authorities are often simply unaware of the needs of elephants. In nature, elephants spend most of the day walking, feeding, bathing in watering holes, and interacting with other elephants, and females live in close-knit family groups for life. In captivity, elephants are separated from their families as babies and sentenced to a lifetime of confinement, boredom, loneliness, and abuse.

Nidhi: What is your reason to keep pushing for change?

Khushboo: Elephants are intelligent, social animals who endure only suffering in captivity. Elephants used by temples, in zoos, for rides, or for any other purpose should be retired and transferred to sanctuaries where they can live unchained in the company of other elephants and heal psychologically and physically from the trauma of years of isolation and captivity. PETA India is already receiving interest from several other temples in Kerala about the possibility of supporting them in the switch to a mechanical elephant, palanquin, or chariot instead of using real elephants.

We at PETA India have had great success in previous campaigns and actions to end the suffering of elephants. Following efforts by PETA India, there are currently no elephants forced to perform in Indian circuses. A few years ago, the Central Zoo Authority, a statutory body operating under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, cancelled the recognition of the Great Golden Circus, the last circus in India which was using elephants for performances. Now, 29 formerly abused elephants rescued from Indian circuses over the past five years are enjoying high-quality lives at a sanctuary. We also rescued, among others, India’s skinniest elephant, Lakshmi, from abuse on the streets of Madhya Pradesh, Gajraj from over 50 years in chains, and Ramprasad from a temple in Maharashtra.

We humans are often a little slow to take on new concepts, but the Irinjadappilly Sree Krishna, Thrikkayil Mahadeva, and Jagadguru Sri Veerasimhasana Mahasamsthana Math temples are paving the way in showing how exciting and effective the use of a mechanical elephant can be. We are confident other temples will follow suit and that mechanical elephants will also be used in weddings and other events – preventing real elephants from suffering.

Nidhi: What’s next in this campaign?

Khushboo: We’re currently in discussions with additional temples, aiming to provide more animatronic elephants and promote compassionate practices across the country. We’ve already signed agreements with four more temples, for which we are currently seeking funding.

While these elephant lookalikes are undoubtedly impressive to behold, their true appeal lies in the fact that they spare real elephants a life of isolation, chains, violent beatings, and exploitation in events that cause them immense torment. With continued support, we’re confident we can create a brighter future for all elephants.